What are connectivity measures?

Connectivity relates to the density of intersections and how direct paths are between places. Increased connectivity reduces the amount of circuitous travel required and often encourages shorter vehicle trips and the use of alternative modes such as biking and walking.

A simplistic measure of connectivity is the connectivity ratio which is calculated by:

- Counting all nonarterial intersections and cul-de-sacs (nodes) in the study area;

- Counting all nonarterial roadway segments (links) between the nodes in the study area; and

- Dividing the number of links by the number of nodes.

A local circulation map is a method to visually examine connectivity. Streets providing local circulation were identified and mapped. The map highlights roads that provide key connections within neighborhoods and commercial centers. This information can then be used to identify areas with lower levels of connectivity. Field visits are conducted to confirm or refine the local circulation map.

Travel model post-processors that work in conjunction with spreadsheet equations and GIS software are used by many planning agencies and consultants to study local connections among employment, shopping, education and other daily travel needs. Some of the more sophisticated tools such as PLACE3S can compare access, connectivity, and multimodal travel benefits of alternative development configurations for a subarea or individual parcel, and then display results with a variety of mapping and graphic tools. Spreadsheet tools have been developed to provide the same analytic rigor without the visualization capabilities.

Who implements connectivity measures?

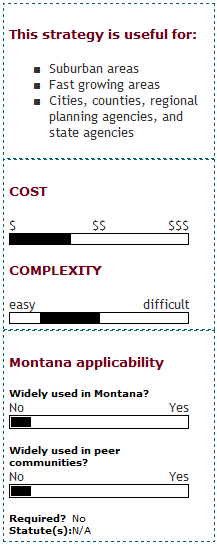

Connectivity requirements can help a locality or region implement its goals for growth management and transportation system performance. They can be included in the MPO long-range planning process and in small urban area plans or access management plans developed by city and/or county governments. Growing suburban areas can use measures of connectivity to help ensure new development includes sufficient infrastructure.

What are the keys to success and potential pitfalls?

Community-based Standards: Communities may differ in their desired levels of connectivity. It would be counter-productive to insist on a rigid connectivity principle applicable to every block. The key is to create strategically located links that benefit broad cross-sections of the community. As respected transportation planner Walter Kulash notes, "The real purpose of connectivity is to provide a variety of routes for daily travel, such as to schools, grocery stores, and after school activities. Kulash further observes: "Proposed street connections that face strong opposition are often a scapegoat for the things people don't like about their community. If you're connecting a quiet old neighborhood to an ugly strip shopping center, people aren't going to like it. Focus on the overall question of what you want for your community." Involving the community in establishing connectivity standards will be important in obtaining acceptance.

Where has this strategy been applied?

Examples in Montana

- The Design and Connectivity Plan for North 7th Avenue Corridor project, completed in 2006, examines redevelopment ideas along North 7th Avenue in the City of Bozeman. North 7th Avenue serves as a major circulation corridor in the city; however, the roadway is primarily auto-oriented at present and is not conducive to pedestrian activity. Although there have been efforts to beautify the corridor through streetscape and landscape improvements in the past, it still falls short of being a pedestrian or bicycle-friendly environment. One of the main purposes of the plan was to develop a design framework for improvement projects along the corridor to enhance connectivity for the pedestrian, bicyclist and automobile to and from adjoining areas of the city. The plan recommends improvements that would help make North 7th Avenue a more vibrant and attractive corridor with its own distinct character through projects that create safe, attractive walkways and streets, enhancements to buildings and landscaping, and improved connections within and to the corridor.

- Missoula's 2001 Non-Motorized Transportation Plan recommends that the community's non-motorized system be continuous to ensure the system is practical and useful. The plan indicates that safe routes connecting major destinations, such as commercial districts, schools and parks, should be developed and that on-street facilities and trails should be interconnected. The plan also includes specific recommendations where trail connections or extensions would be desirable.

Examples outside of Montana

- VDOT Secondary Street Acceptance Requirements: The Virginia Department of Transportation uses a connectivity index as part of its Secondary Street Acceptance Requirements (SSAR). The rules govern the design of streets by private sector developers for acceptance into the public street system.

- City of Calgary Local Transportation Connectivity Study: This study included recommendations for street connectivity and accessibility requirements.

- Town of Cary, NC Connectivity Index

- Street Connectivity Standards Change, Portland Metro, 2001

How can I get started?

A first step toward measuring connectivity is to develop an inventory of the local street network. Using GIS, a community can map the links and nodes (intersections) in order to calculate the existing connectivity ratio. To establish a connectivity ordinance, it is helpful to start by researching the small but growing number of successful ordinances around the country.

Where can I get more information?

- Making the Connection, by Hannah Twaddell, Planning Commissioner's Journal Issue #58, Spring 2005.

- Roadway Connectivity, TDM Encyclopedia, Victoria Transport Policy Institute,

- Planning for Street Connectivity: Getting from Here to There. Planning Advisory Service Report #515, American Planning Association